FROGS: Facing a Changing World

The intriguing world of amphibians connects ecosystems, reflects a rich natural history, contains enormous diversity, and gives a glimpse at future environmental impacts.

Frogs have captivated cultures around the world. They are the source of myths, stories, legends, and play a significant role in popular culture. They are colorful, diverse, and have a fascinating biology that reflects their unique vulnerability to our changing world.

Frogs and their amphibian relatives have a unique life cycle, living part of their lives in water and the other on land or underground with a few exceptions. These small vertebrates need water or a moist environment at some point in their lifecycle to survive. Wetlands, rainforests, rivers and streams, deserts, and mountains are all homes to amphibians. Most might imagine a frog or toad as the typical amphibian; however, amphibians also include salamanders, newts, and the limbless caecilians.

Amphibians eat small animals while also being an important food source for fish, birds, and snakes. They connect the lower levels of the food chain to the higher levels, serving an important role in ecosystem health. Amphibians have many amazing adaptations. Some have the ability to breathe through their skin or secrete a mucus layer to stay moist, and some have specialized fingertips to climb.

“

We’ve been very fortunate to have so much diversity on our shared planet. We need to work hard to preserve it.

—

Rob Mortensen, Aquarium of the Pacific’s assistant curator of mammals and birds

”

California Newt (Taricha torosa) | Robin Riggs/Aquarium of the Pacific

Metamorphosis

Amphibians experience a spectacular series of changes in their life cycle, truly representing the word metamorphosis.

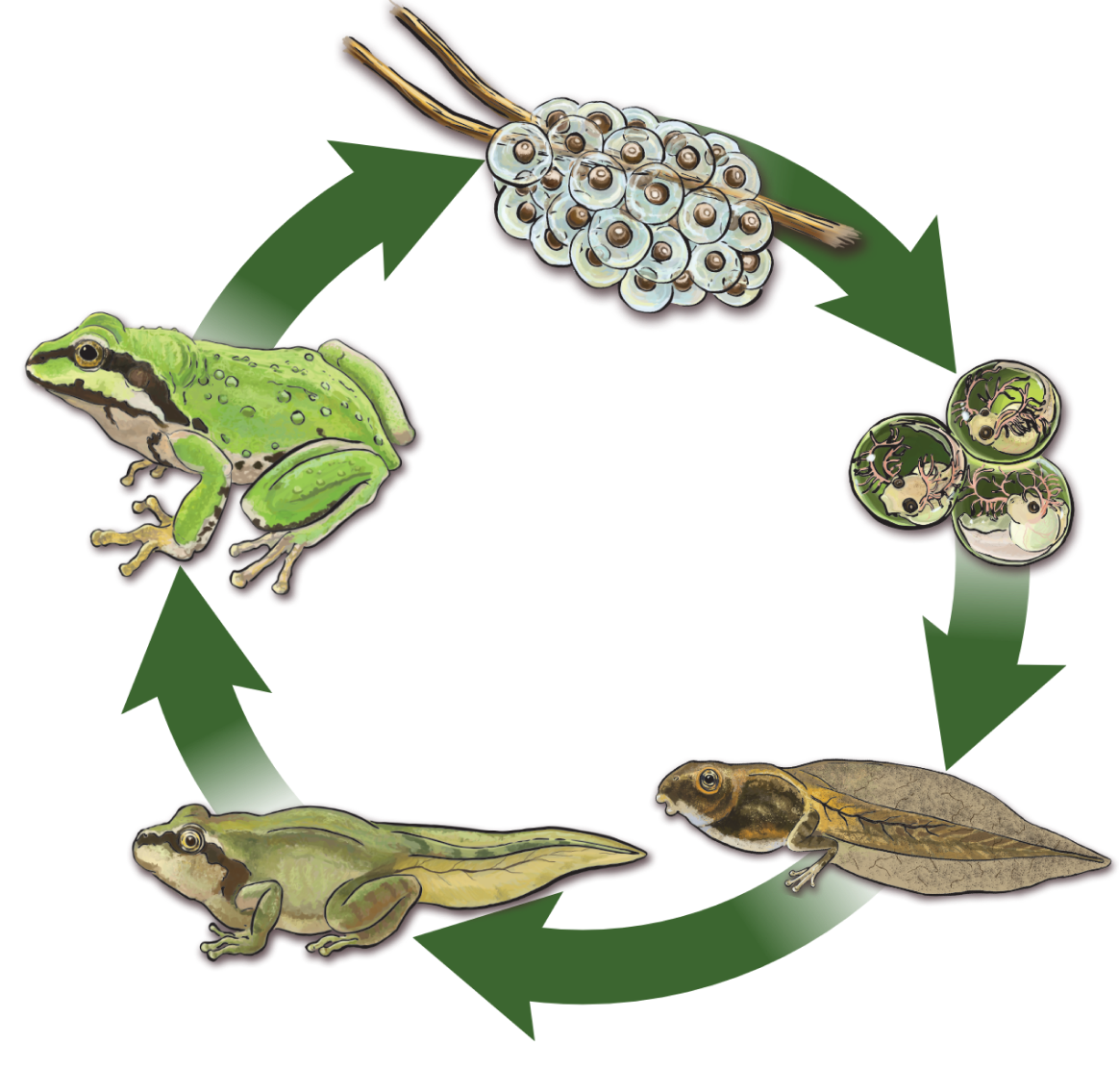

Frog lifecycle: (clockwise from top) eggs, embryos, tadpole, froglet, and adult.

In the water, many amphibians lay eggs en masse of anywhere between 500 to 2,000 eggs. Two to three weeks later those eggs will hatch into tadpoles. The time is dependent on the temperature of the water and the species. Depending on the species, the tadpoles will transform into an adult. Many amphibians stay fully aquatic or underground and are built to move in and out of the water.

Tadpoles begin as small, free-swimming animals resembling fish. At this stage, the tadpoles have gills. Slowly skin grows over the gills. Next, the tadpole’s teeth will grow, and hind legs begin to appear. It is beginning to look more like the adult amphibian. Finally, front legs grow in, and it becomes a juvenile or froglet depending on the type of amphibian.

Mountain yellow-legged frog tadpoles | Robin Riggs/Aquarium of the Pacific

At this young stage, most species will complete the metamorphosis process. However, some species, such as the axolotl, will remain at this larval stage called “neotenic” for their entire lives. Salamanders and newts retain their tails, while frogs and toads absorb their tails as they metamorphose into adults.

Sonoran desert toad (Incilius alvarius) | Robin Riggs/Aquarium of the Pacific

Ancients

Modern frogs as a group are estimated to be around 200 million years old, which means frogs lived alongside dinosaurs. During that time, the diversity of frogs was not very high, but they were widespread. They did not resemble frogs as we might identify them today.

Older frog species like the Triadobatrachus had more vertebrae but did have a skull like the modern frog with bones arranged in a lattice separated by large openings. After the dinosaurs went extinct, the diversity of frogs increased. During this period is when frog species like the tree frog made their appearance.

Around 180 million years ago, newts made their first appearance. Newts spend more time in the water than most frogs, toads, and salamanders and have well-developed webbed feet to help them move. Some newts can secrete a tetrodotoxin, which is the same potent toxin found in pufferfish.

Sixteen million years later, the salamanders began to crawl on land. Salamanders typically lack the webbing between the toes found in newts. The axolotl is a species of salamander that has evolved in recent evolutionary history, dating back to about ten thousand years old.

Mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) | Robin Riggs/Aquarium of the Pacific

Changing World

The effects from climate change have impacted many amphibians. They are an indicator species, that is to say they can help determine the health of the ecosystem.

Since they rely on both water and land to complete their lifecycle, amphibians are often one of the first animals to disappear when environmental effects begin to grip the ecosystem. The combination of extreme wildfires and rainfall Southern California experiences each year can decimate local populations, such as is the case for California’s mountain yellow-legged frog.

Climate change has the largest, most widespread impact on amphibians and can be compounded by other impacts, including habitat destruction; a deadly disease caused by chytrid fungus; invasive species that can eat, outcompete, spread disease, and hybridize with native species; and pollution, which can affect them in their aquatic and terrestrial phases.

“

The Aquarium of the Pacific’s abilities and willingness to involve communities in local conservation is an invaluable tool in the effort to save species and habitat.

—

Rob Mortensen, Aquarium of the Pacific’s assistant curator of mammals and birds

”

Hope

Despite threats, there is hope for frogs and their amphibian relatives. We can all reduce the effects of climate change and reduce pollution.

Institutions like the Aquarium of the Pacific can help with species recovery. The Aquarium has already helped rear tadpoles and has released over 300 mountain yellow-legged frogs into their natural habitat in our local mountains, making a meaningful impact on saving this species from extinction.

Red-backed poison dart frog (Ranitomeya reticulata) | Robin Riggs/Aquarium of the Pacific

FROGS: Facing a Changing World

There are many amphibians to learn and care about, which is the focus of the new exhibit FROGS: Facing a Changing World opening May 24, 2024, at the Aquarium.

Guests can connect to amphibians that live in our own backyard, including the mountain yellow-legged frog; discover vibrant habitats featuring colorful tropical frogs from around the world; peek behind-the-scenes to watch staff care for frogs from eggs to adults in a nursery; see a new exhibit space highlighting California and Baja frogs, their amphibian relatives, and reptile neighbors; and even paint your own virtual frog.

You will learn about the diversity of species and their unique adaptions, the threats they are facing, and how the Aquarium is helping to save them from extinction.